The following is a paper submitted to Dr. Kevin Vanhoozer in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the course ST 7505 Use of Scripture and Theology at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School in December 2015 in Deerfield, Illinois.

The full title of the paper is The Use of Scripture in Evangelical Political Proposals – A Case Study: Comparing, Contrasting, and Analyzing Jim Wallis and Wayne Grudem’s Use Of Scripture to Authorize Their Distinct Approaches to Economics.

Note: I’m not the proudest of this paper. Due to time restraints I was forced to write it in the timespan of merely two days. Nonetheless, I share it in case anyone may benefit from it by its prompting critical reflection. I only ask they you read with an extra dose of grace on this one. Thank you.

Introduction

“Our guys won!” Those were the words of one of my fellow church members after Republican candidates largely swept their Democrat counterparts in the 2014 midterm elections. A neither small nor insignificant assumption was present in her statement: the Republican candidates were the evangelicals’ candidates; a victory for the Republicans meant a victory for Christendom.

Such a wedding of the religious right with the political right is not uncommon in the American evangelical consciousness, and, by extension, the perception of the popular culture at large. For example, if one listens consistently enough to Albert Mohler’s daily broadcast The Briefing,[1] one will be repeatedly “informed” that the ultimate difference between the political right and political left is one of worldview: progressive policies are spawned out of what is an unqualifiedly non-Christian worldview (either that or political liberalism is equated with theological liberalism) while political conservatism is described in such terms (and without nuance) so as to lead one to believe it is essentially a Christian (evangelical) worldview gone political.

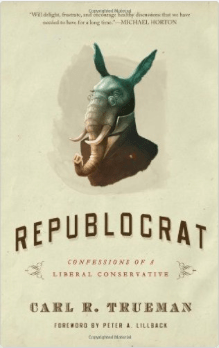

One can trace this formalized “hypostatic union” of evangelicalism and republicanism—deeming theological conservatism and political conservatism “equally yoked,” and “deifying” the political right in the process—back to (at least) the emergence of the Moral Majority movement beginning in the 1980s with Christian leaders such as Jerry Falwell. However, authors such as Carl Trueman in his work Republocrat: Confessions of a Liberal Conservative challenge this “sacramental union” as “accident” not “essence.” As Michael Horton writes in his recommendation to Trueman’s work,

Carl Trueman points out in his witty, provocative, and deeply well-informed way [that] the alliance of conservative Christianity with conservative (neoliberal) politics is a circumstance of our own context in U.S. politics—neither historically nor logically necessary.[2]

“Amen, amen!” says fellow Brit N.T. Wright:

The combinations of issues [i.e., the bundling up of certain political issues as “conservative” and others as “liberal” and binding evangelicalism to the former] seem to make sense in America, but they don’t make sense to many people elsewhere in the world. . . .[3]

[T]he political spectrum in the United Kingdom, and indeed in Europe, is quite different from the spectrum in the United States. In Britain, issues are bundled up in different ways than in America. What’s more, over the last forty years, those in the United Kingdom who have tried to integrate faith and public life have mostly been on the left of the spectrum, while those who have done the same in the United States have tended to be on the right.[4]

“The British are coming! The British are coming!” and they are challenging our American political-religious bundlings in the process.

But lest we think these Brits are just off their rockers, interestingly a 2007 study by Baylor Religion Survey found that the more frequently one reads the Bible the more likely one is to lean politically liberal on certain issues. And, statistically, those who read their Bible’s most were found to be evangelicals—the stereotypical political conservatives. Expectedly, frequent Bible reading correlates with opposition to abortion and gay marriage. But it also surprisingly (at least given the contemporary stereotype of evangelicals) has the effect of making readers more prone to agree with political liberals on issues like criminal justice, the death penalty, environmental conservation, and, most interestingly for the purposes of this paper’s case study, social and economic justice. These results hold true “even when accounting for factors such as political beliefs, education level, income level, gender, race, and religious measures (like which religious tradition one affiliates with, and one’s views of biblical literalism).”[5]

Continue reading →

The use of abortion as a wedge issue and as a clear dividing line between Republican and Democratic parties

The use of abortion as a wedge issue and as a clear dividing line between Republican and Democratic parties