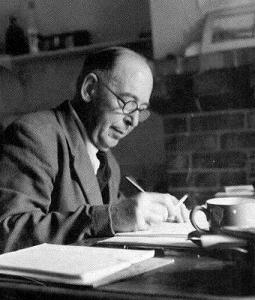

I’ve been reading Mere Christianity by C.S. Lewis lately. Over the next few weeks I plan on sharing some sections with some occasional commentary. (If you follow me on social media [Facebook; Twitter], you will see that I will be sharing some quotes there too.)

In Mere Christianity Lewis makes the following comment:

You cannot find out which view is the right one by science in the ordinary sense.[1] Science works by experiments. It watches how things behave. Every scientific statement in the long run, however complicated it looks, really means something like, ‘I pointed the telescope to such and such a part of the sky at 2:20 a.m. on January 15th and saw so and-so,’ or, ‘I put some of this stuff in a pot and heated it to such -and such a temperature and it did so-and-so.’ Do not think I am saying anything against science: I am only saying what its job is. And the more scientific a man is, the more (I believe) he would agree with me that this is the job of science–and a very useful and necessary job it is too. But why anything comes to be there at all, and whether there is anything behind the things science observes–something of a different kind–this is not a scientific question. If there is ‘Something Behind,’ then either it will have to remain altogether unknown to men or else make itself known in some different way. The statement that there is any such thing, and the statement that there is no such thing, are neither of them statements that science can make. And real scientists do not usually make them. It is usually the journalists and popular novelists who have picked up a few odds and ends of half-baked science from textbooks who go in for them. After all, it is really a matter of common sense. Supposing science ever became complete so that it knew every single thing in the whole universe. Is it not plain that the questions, ‘Why is there a universe?’ ‘Why does it go on as it does?’ ‘Has it any meaning?’ would remain just as they were?

C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, book 1, chapter 4, paragraph 2 (emphasis added).

In short, Lewis is pointing out that science has a particular domain, and as such, has a limited object of study. It cannot, by definition of being that discipline which studies the observable (not the non-observable), reach outside of the observable into the realm of the non-observable (e.g., God) or into matters of meaning, e.g., why the observable is the way it is.

To be specific, Lewis’ comments serve as a rebuke to those who adapt the following sorts of arguments:

- I believe what we can know through science (observation).

- Science cannot observe God.

- Therefore, God does exist.

(Besides the fact that this sort of argument is non sequitur) what this sort of argument fails to recognize is the limited domain of scientific study (i.e., it is limited to the observable). This form of argumentation makes a huge assumption–that science is not merely a means of gaining knowledge, but the means (i.e., the sole means) of gaining knowledge. But this is merely to preclude a prior–not by demonstration or argument, but simply out of hand, without any justification–all other means of inquiry.

Notes

[1] Here Lewis is referring to the following two views: on the one hand, a view that all there is is the material world and that there is no God, for instance (what he calls “the materialist view”), versus a view, on the other hand, that holds to a belief in a God who in some way stands behind the material world (“the religious view”).

C.S. Lewis provides a great explanation to the accusation that God’s love must be selfish if God seeks it for His own glory when Lewis says,

C.S. Lewis provides a great explanation to the accusation that God’s love must be selfish if God seeks it for His own glory when Lewis says,